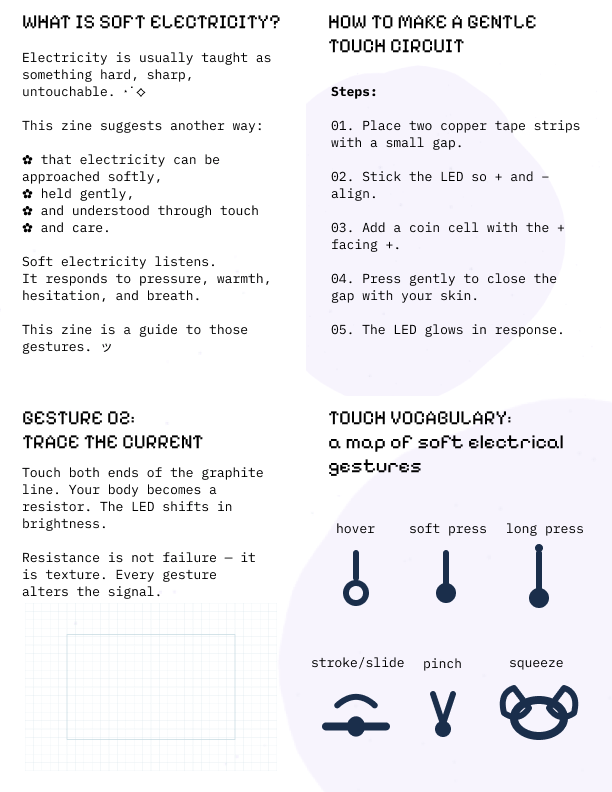

sailor moon inspired riso animation

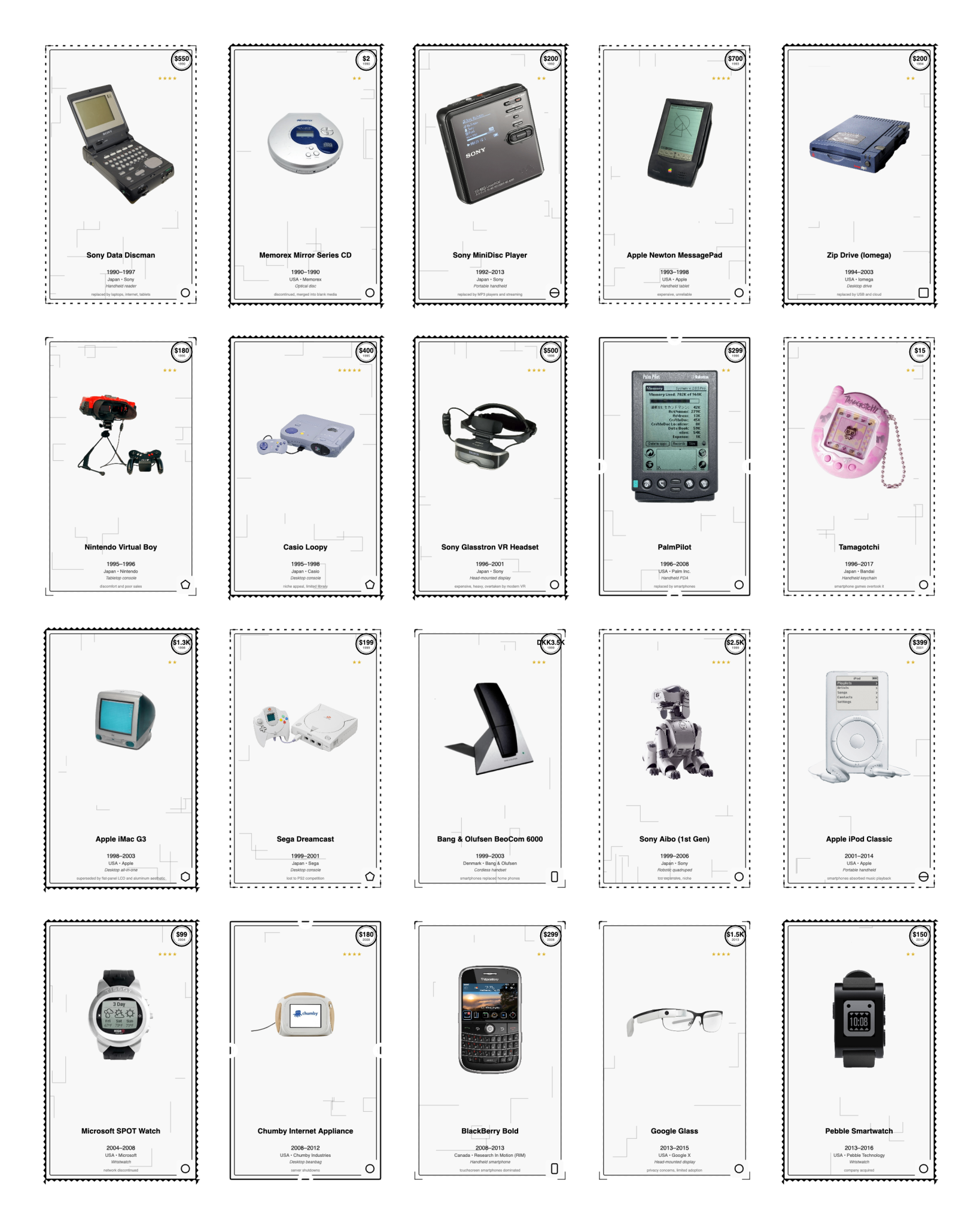

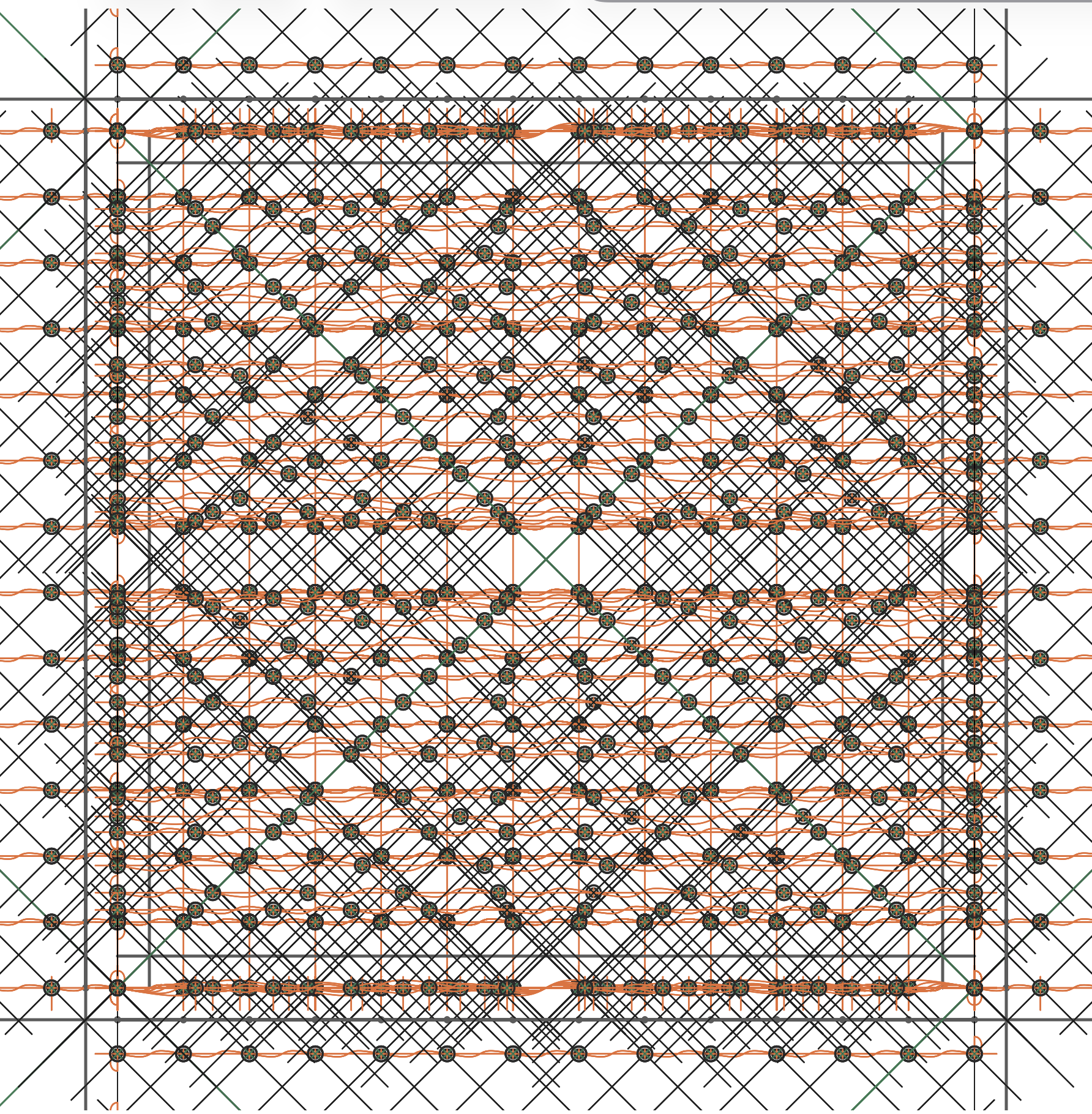

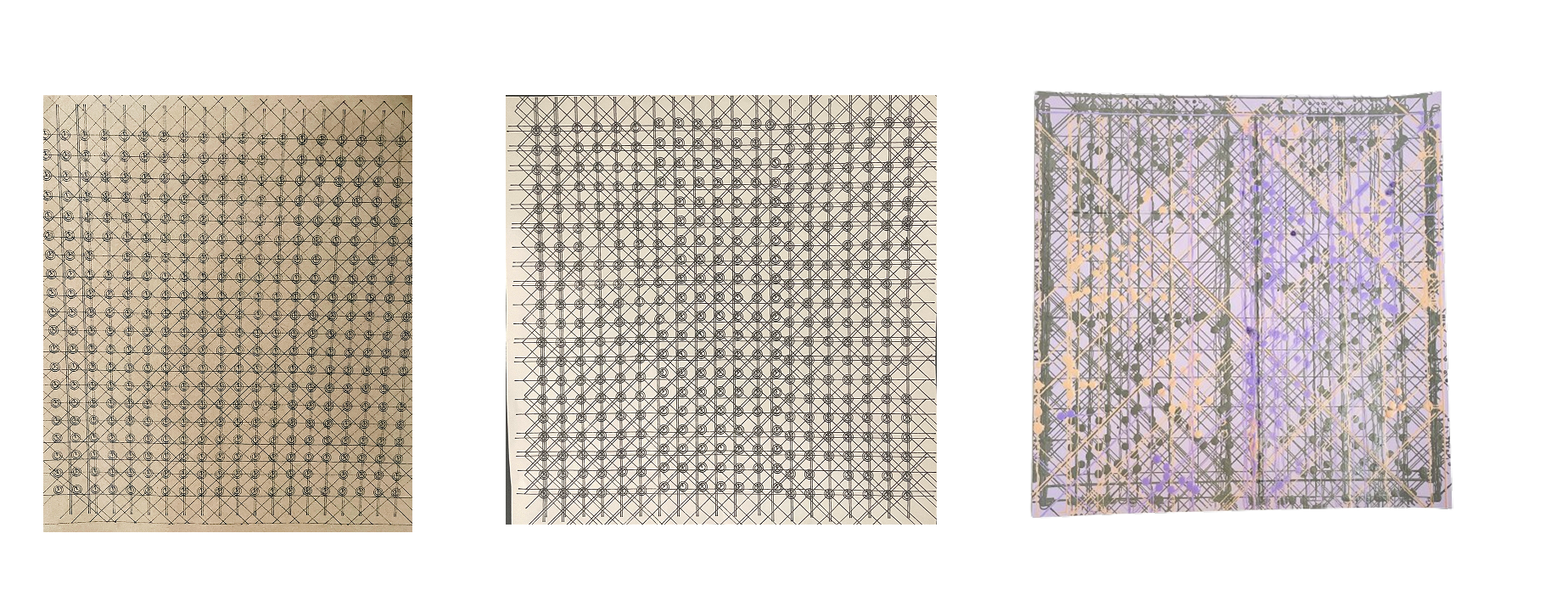

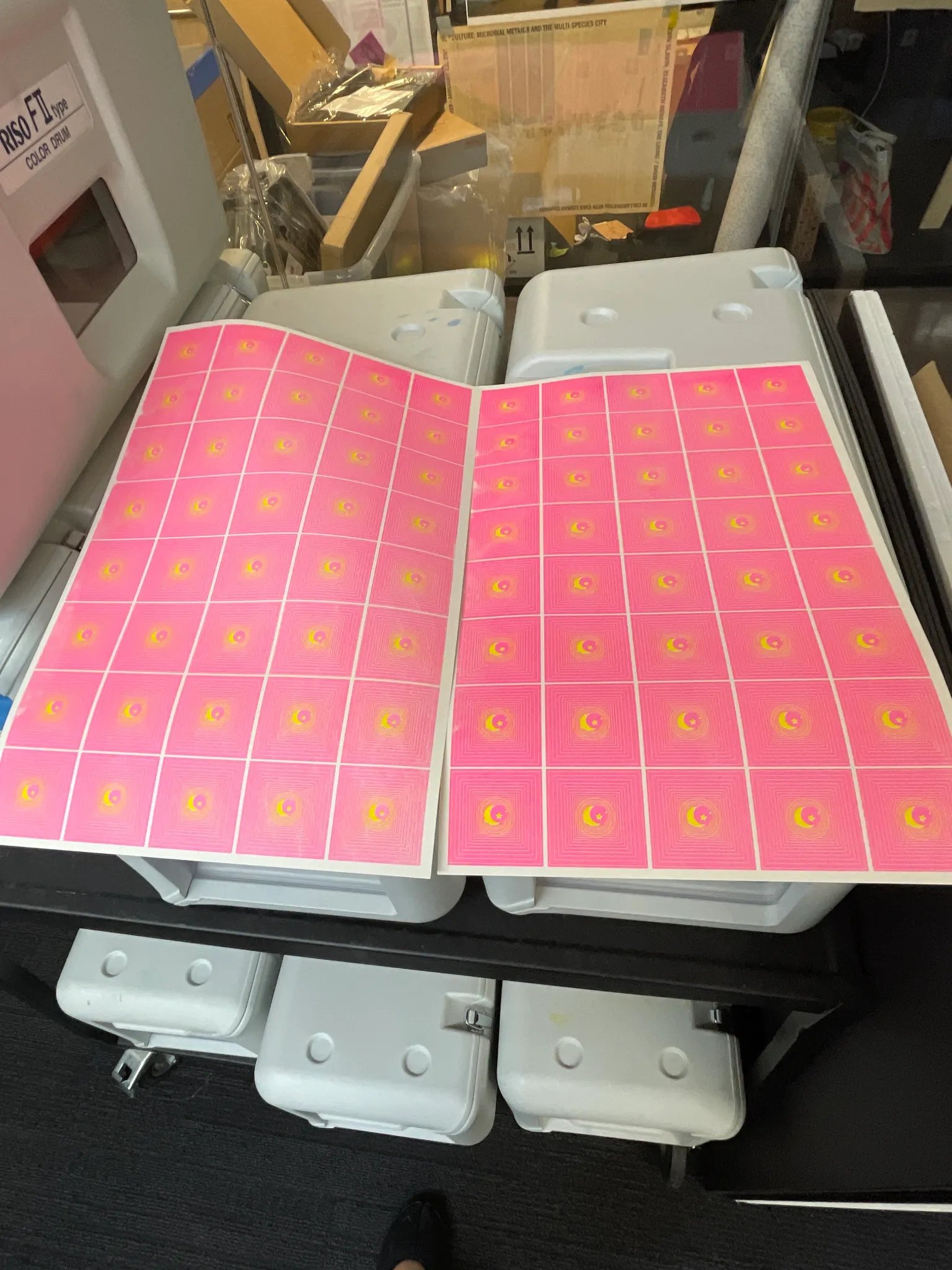

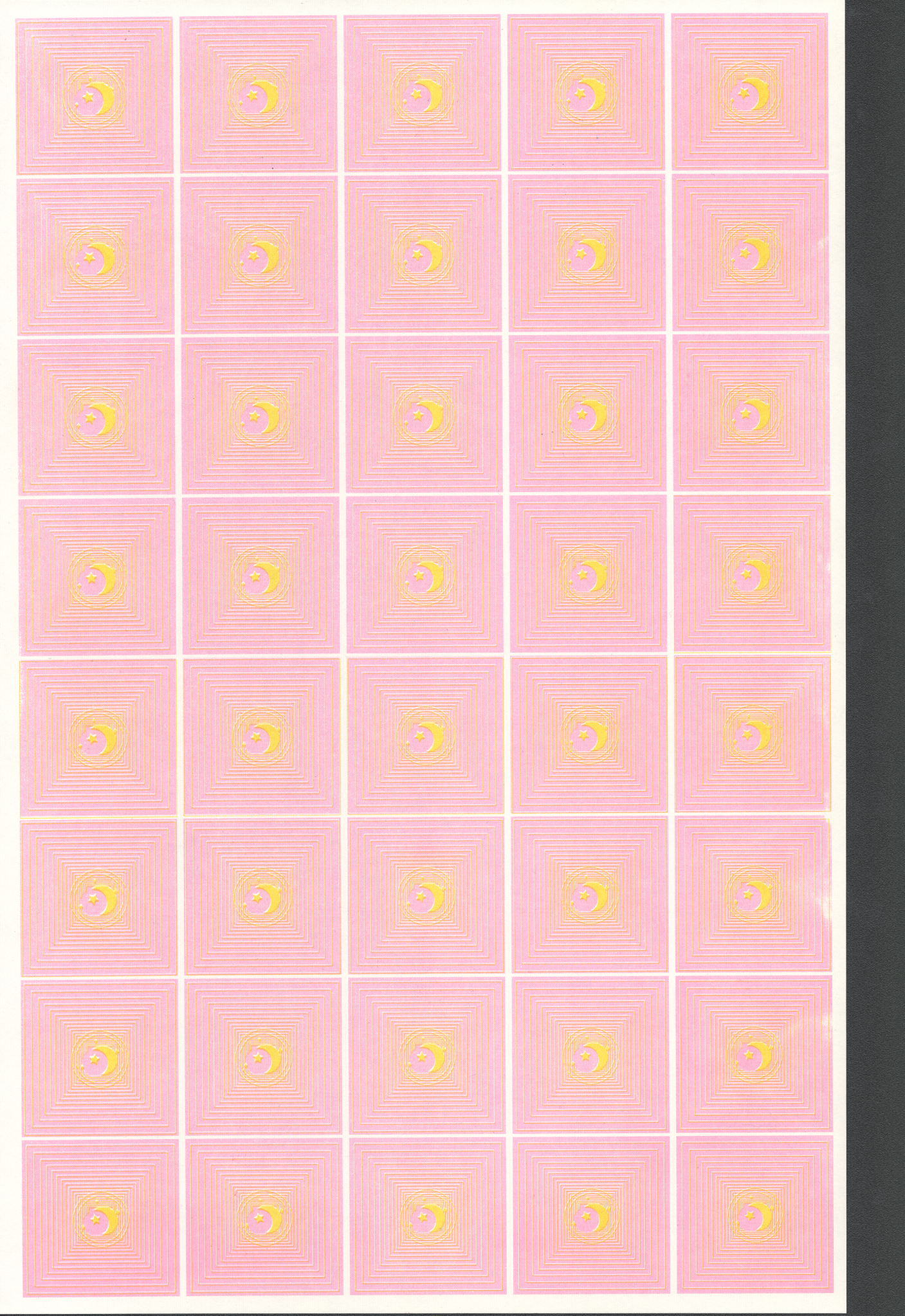

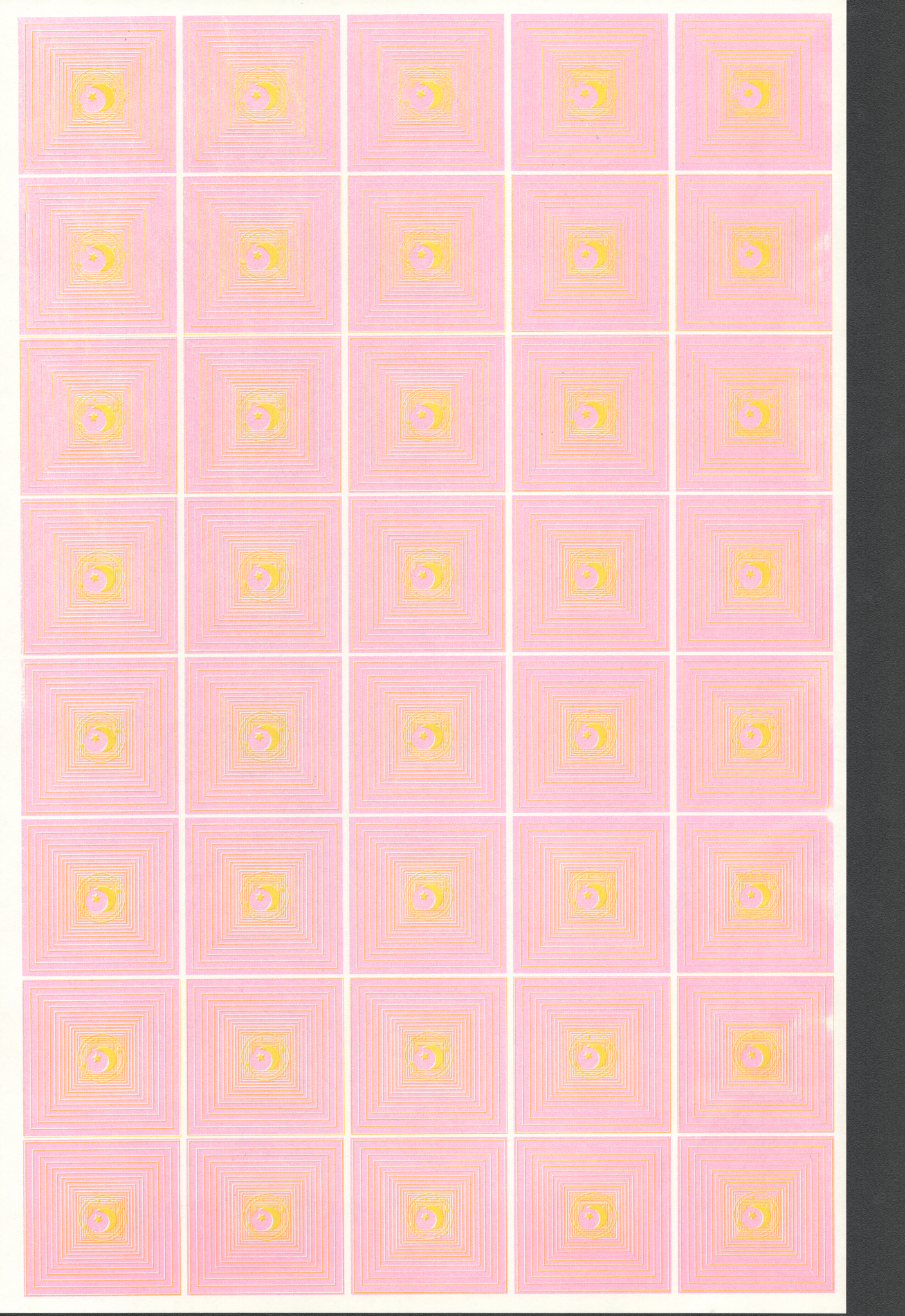

For this project I created a Sailor Moon inspired risograph animation. Sailor Moon was my favorite anime growing up, so it felt natural to return to it as a source of visual language and nostalgia. The main element I animated was the star symbol, which rotates as the central motion. At first I experimented with bold, bright colors, but once I printed it I realized they came out much harsher than expected. That was a surprise, something that looked more soft and luminous on screen appeared almost overwhelming in print. This led me to make a second version with pastel tones.

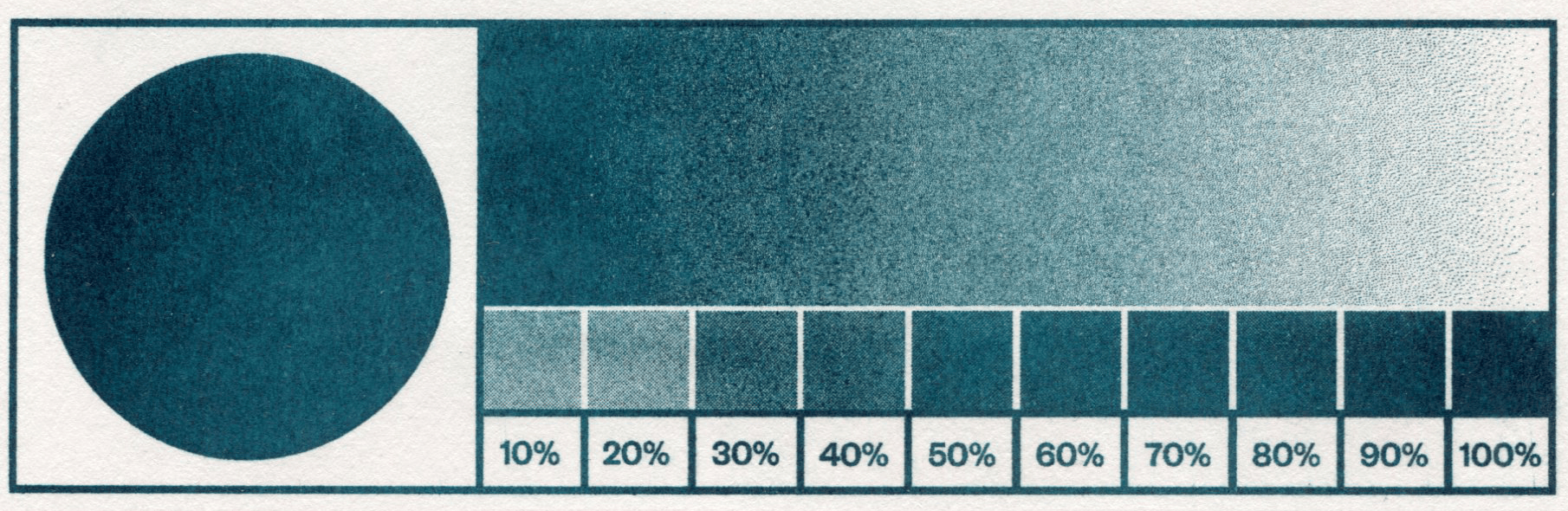

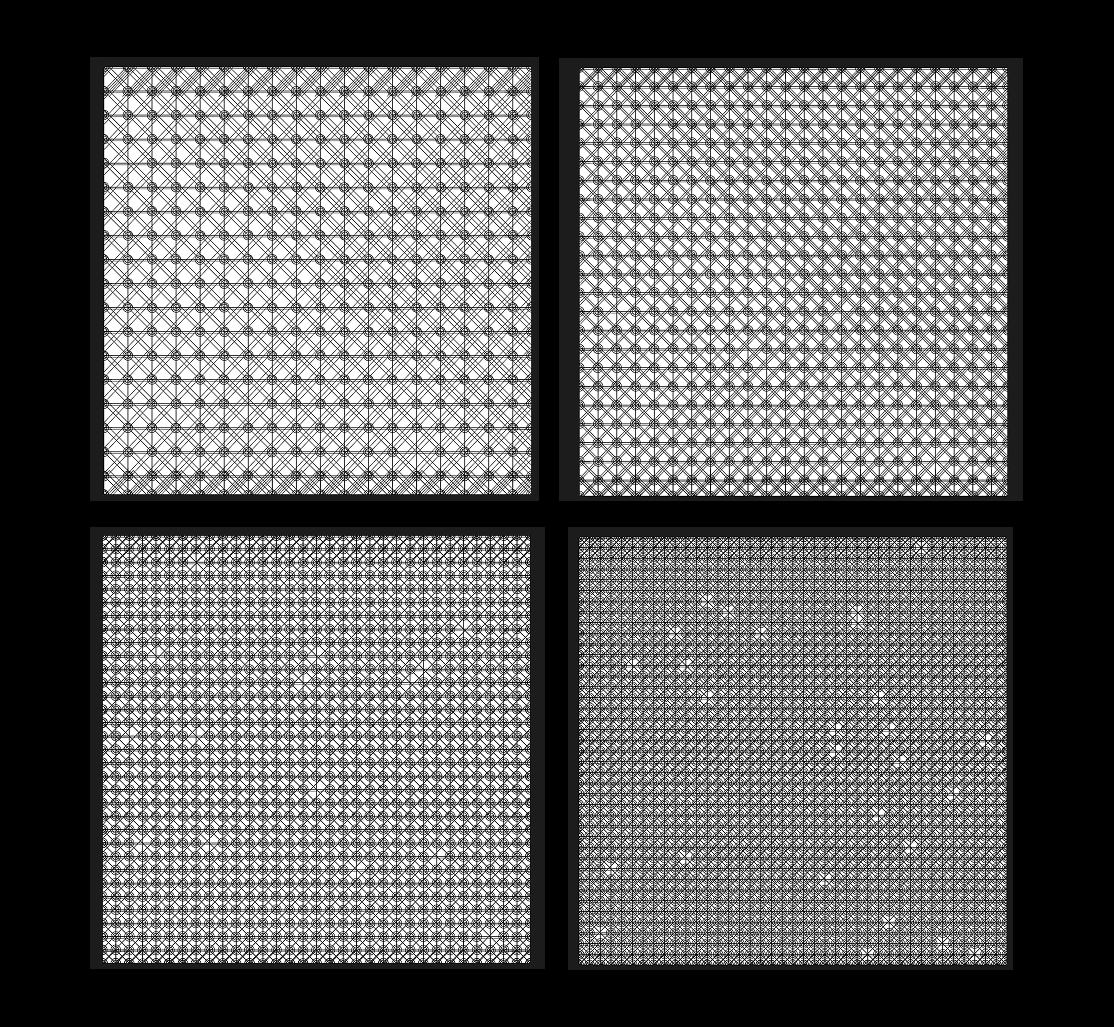

I like that the adjusted yellow and gold almost resemble a stamped texture, which gives the piece a tactile quality. Another detail I especially enjoy is the dithering effect produced by the risograph process. The halftone dots and gradients create a textured look that makes the animation feel layered and physical, giving it a softness that could not be fully replicated digitally. It also connects back to the retro anime and manga aesthetic of Sailor Moon itself, which often used screen tones and grainy textures to create atmosphere.

Digital vs Analogue Workflows

The production process highlighted the difference between digital and analogue workflows. In my p5.js sketch, the animation feels smoother and more dynamic because the code generates movement continuously. Translating that into a frame-based risograph sequence required me to limit the motion to discrete stills. I ended up producing many frames, but paradoxically the effect was less animated than my original sketch. It made me think more carefully about how few frames are needed to suggest motion effectively, and where excess becomes static.

Glitch and Noise

The process also connected to our readings on glitch and noise. In the translation from screen to print and back to screen (digital → analog → digital), unexpected forms of noise appeared. Color shifts, uneven textures, dithering, and slight misalignments worked as glitches that added character. Instead of being errors, these became aesthetic features, reminding me of how compression artifacts or VHS static, once considered flaws, now read as nostalgic or stylistic choices. I was surprised by how much I welcomed these "imperfections." They gave the animation a tactile richness that my p5 version lacked.

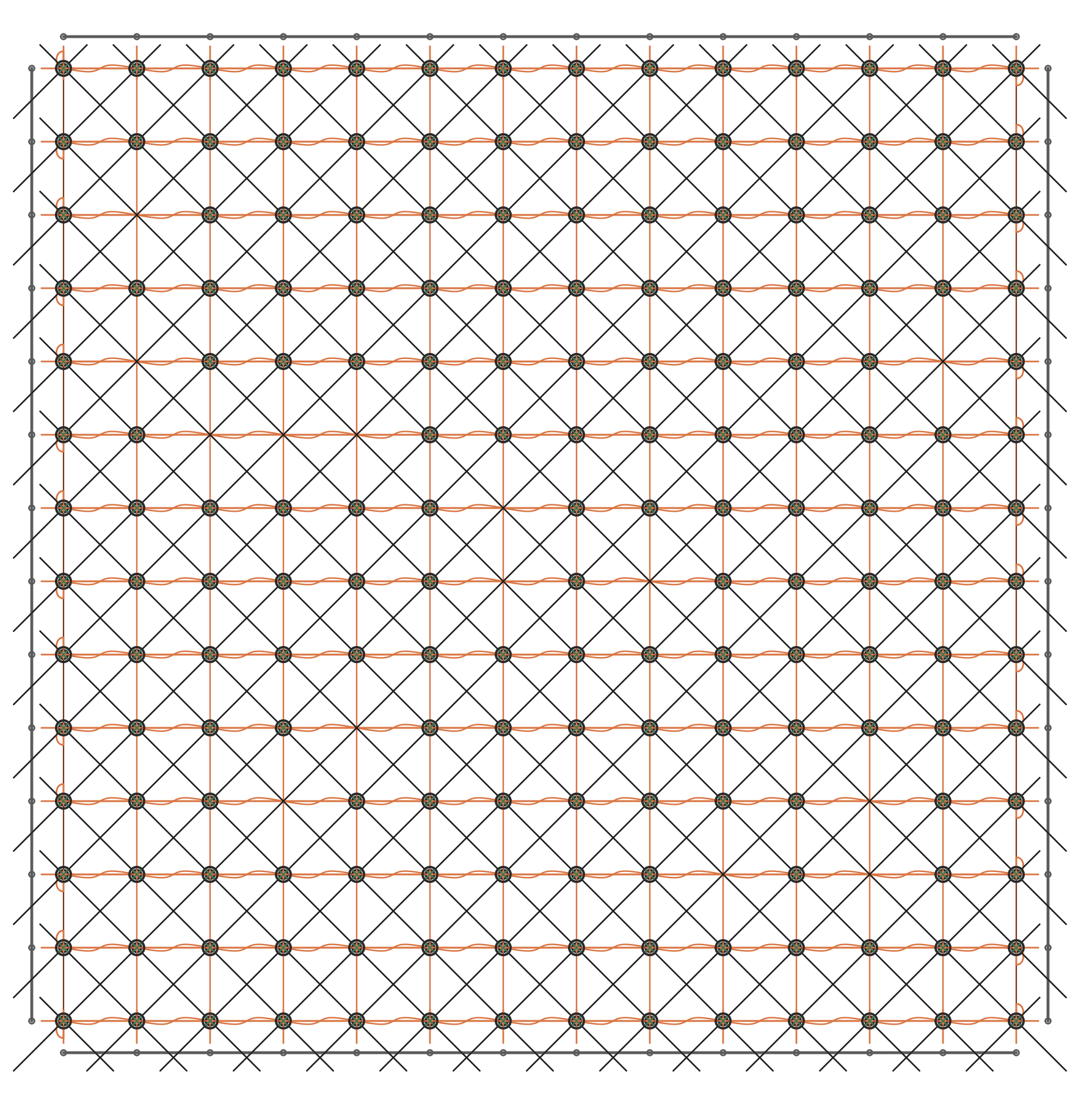

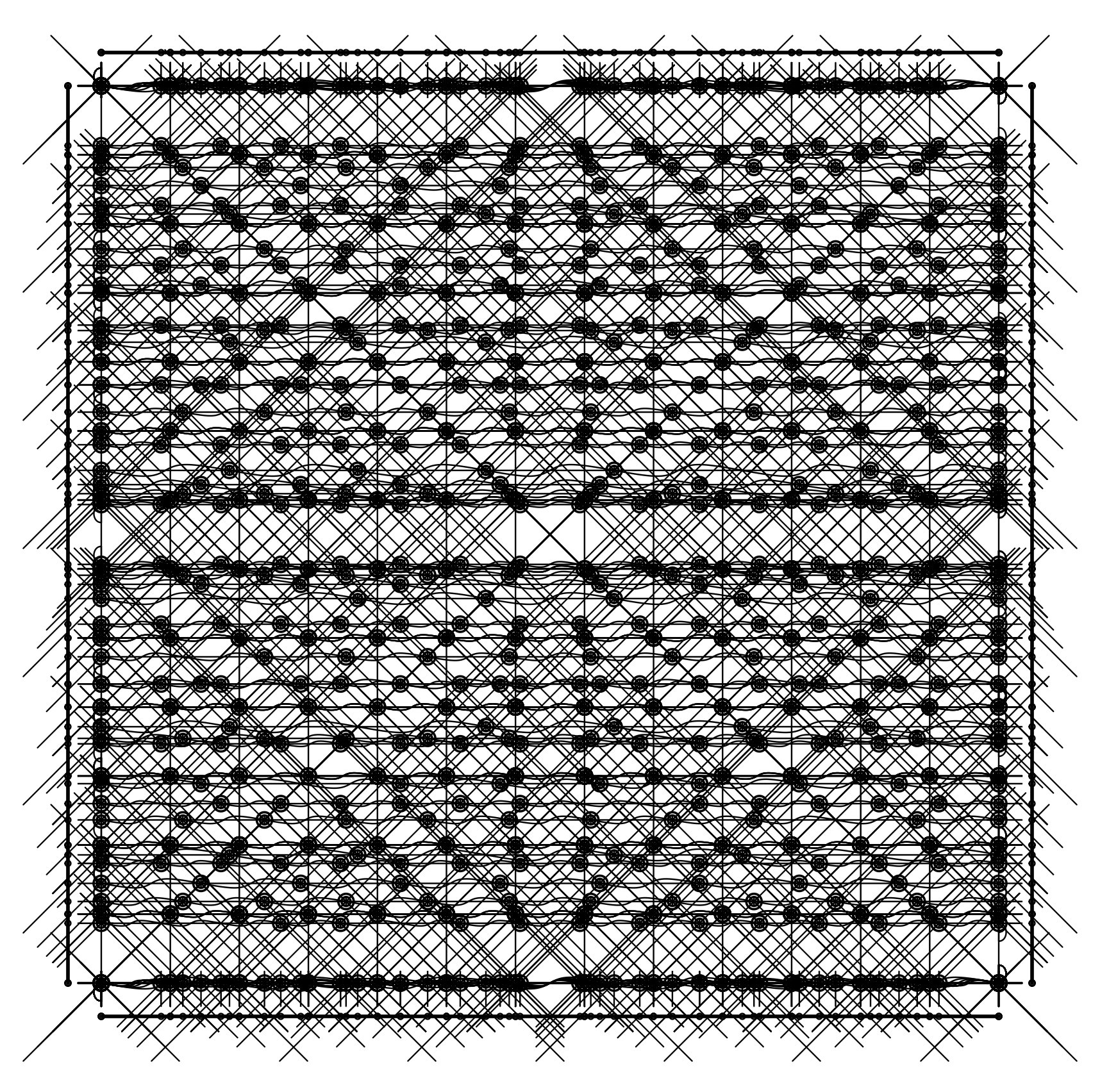

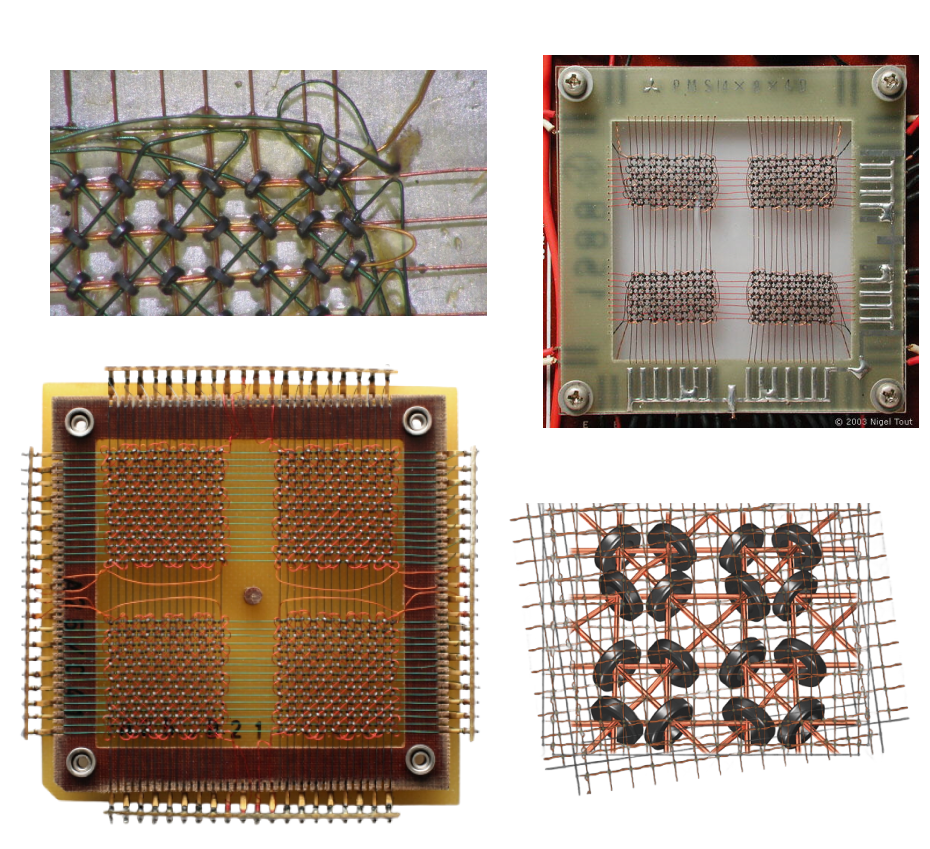

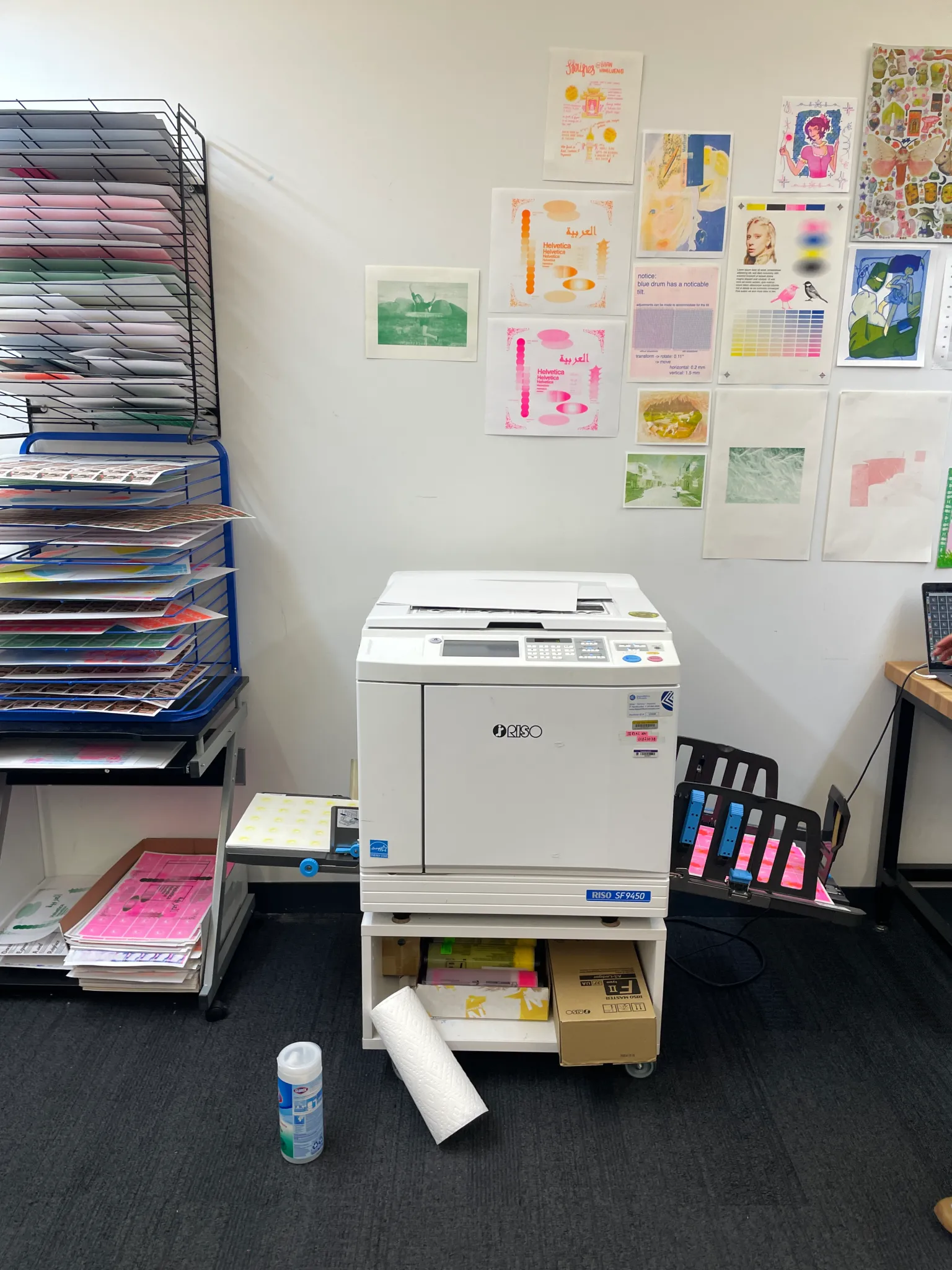

The Actual Process: The process moved through several stages across both digital and analog tools. I first developed the sketch in p5.js, testing out colors, movement, and frame counts in code. Once I had the star animation working digitally, I separated the frames and prepared them for print at the riso lab. Printing was its own experiment—colors shifted, layering created unexpected textures, and the dithering patterns emerged through the risograph's limitations.

After printing, I scanned the individual frames back into the computer and compiled them in Adobe Photoshop, where I built contact sheets to organize the sequence. From there, I assembled the frames into an animation, layering them back together into a moving loop. Each step introduced its own character: coding produced smooth continuous motion, printing introduced tactile noise and color shifts, scanning translated those textures into pixels, and finally Photoshop restructured the sequence into a cohesive animation.

Reflection

I would probably recreate this animation again and try my best to cut the frames so it won't have such a wobbly effect. Nonetheless I am content with the riso texture it brings to life.

Reflecting on this project, I see glitch and noise not as disruptions but as collaborators in the process. They make the work feel less polished and more human, carrying traces of the materials and machines involved. That tension between my controlled digital sketch and the noisy analogue print revealed how animation can live across mediums, each step introducing its own unexpected variations. Ultimately, this project reminded me that part of animating is allowing the process to transform the image, even when it veers away from what I initially imagined.